John Reginald Holt

Clemency for John Reginald Holt

Northern District of Texas (Fort Worth Division) Case No. 4:09-CR-115-A'

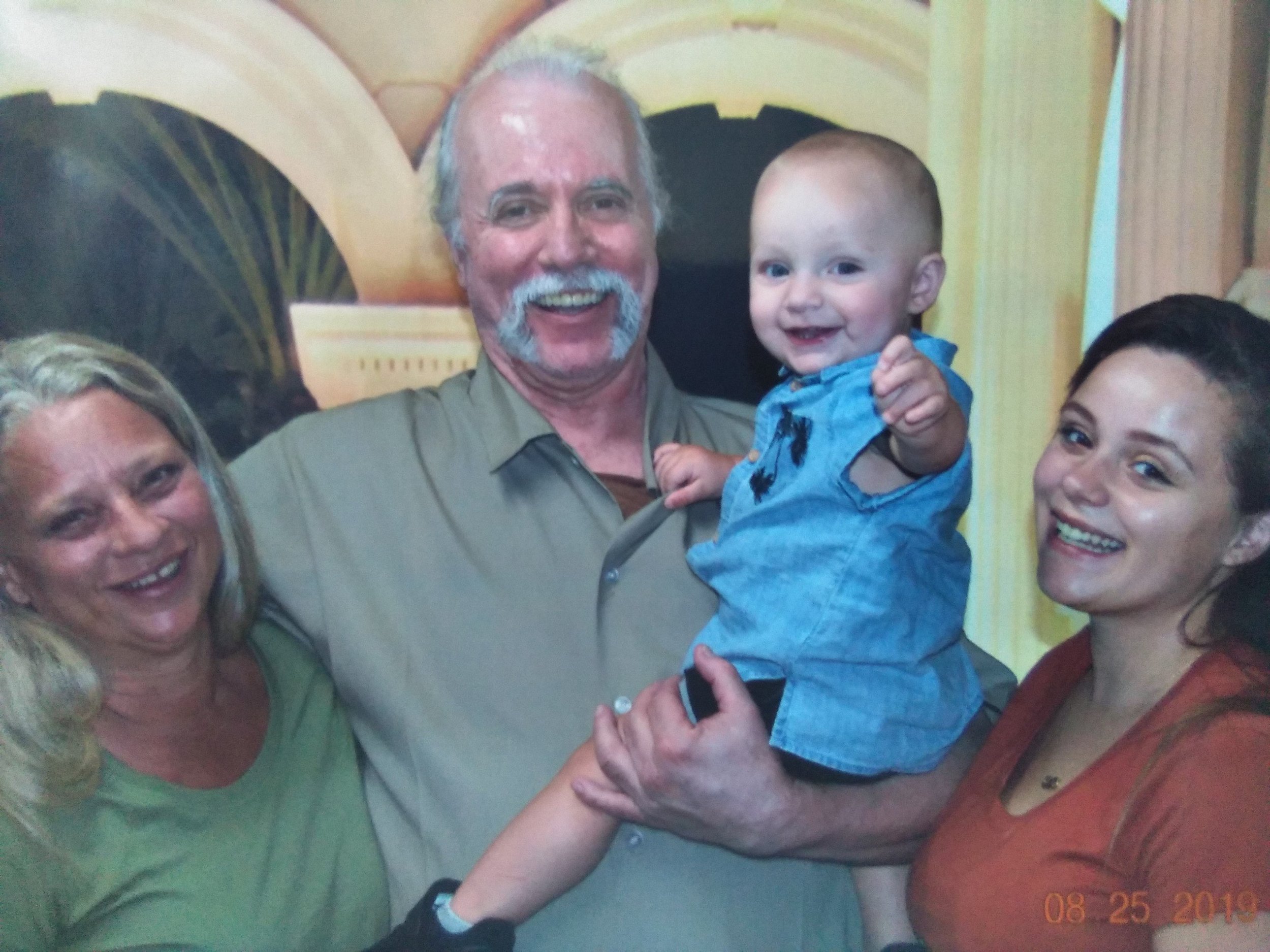

John Holt is a 66-year-old grandfather. (John has been married about 35 years; he has four daughters and a son as well as seven grandkids.) Until now, he’s never been to prison. He has no felony convictions, and he’s been in prison for nearly 14 years. He was given a 30-year federal sentence for a nonviolent drug offense. Since there is no parole in federal prison, John Holt is likely looking at a de facto life sentence. Put bluntly, he will probably die in federal prison.

When most people think of drug kingpins who distribute millions of dollars of drugs each year (in this case, according to the government, about $7.5 million worth of methamphetamine over 16 months), they almost certainly envision someone who is living in a mansion, someone who has a collection of luxury cars—you know, someone with all the trappings of “success.” Perhaps the kingpin owns several businesses and even has a horse farm—or owns beautiful racehorses. The quintessential kingpin likely takes expensive vacations, jetting all over the world.

John Holt was no kingpin. Now approaching his 70s, back then, he was a fifty-something-year-old drug addict who lived in an old, broken-down camper that he bought for $600 at a Goodwill auction. He did not own a vehicle, much less a collection of luxury cars, and he didn’t even have a bank account. And even more tellingly, according to the testimony of the investigating government agents during his trial, when they tried to wiretap his cell phone, his phone was turned off for “nonpayment.”

Photo right: The $600 camper that John (sentenced to 30 years in federal prison for distributing $7.5 million in methamphetamine over 16 months) lived in.

John couldn’t even pay his phone bill.

The truth is, John was an errand boy for the drug kingpin. The undisputed drug kingpin in the case was a man called Hammer. Unlike John, Hammer did own homes and businesses, and he did have a collection of luxury cars and motorcycles. John mowed his lawn, acted as his driver, made repairs to his home, looked after his home when Hammer was away, and so on. Hammer also used John to carry out the drug deals that occurred at his (Hammer’s) home. As the trial transcript reflects, customers would come to Hammer’s home, John would take them to a room, provide Hammer’s drugs to them, take the money, and put it in an envelope, which was then given to Hammer. John was something of a cashier, an instrument of Hammer.

In return for his service, John was not paid a portion of the drug proceeds. Instead, he was allowed to drive Hammer’s cars, sleep at Hammer’s home from time to time, as well as pocket a $250 paycheck every two weeks (for his work around Hammer’s house). He was also given small amounts of methamphetamine to fuel his addiction.

Without any factual support, John’s Presentence Investigation Report (PSR) simply states that in 2008, Hammer’s drug operation distributed 5 pounds of methamphetamine a week for 52 weeks (1 year) and 3 pounds of methamphetamine per week for the 17 weeks (four months) that John worked for Hammer in 2009, for a total of 311 pounds (or 141 kilograms) of methamphetamine. The massive drug amount drove John’s U.S. Sentencing Guideline range to 30 years in prison to life in prison. As a result, John received a 30-year federal prison sentence. (Notably, John was never caught with any drugs.)

For perspective, based on conservative pricing of methamphetamine during that time, the government said that John is responsible for distributing about $7.5 million in methamphetamine in a little more than a year (about 16 months)—the same John Holt who lived in a dilapidated $600 camper, who didn’t have a vehicle to drive, who couldn’t even scrape up enough money to pay his monthly cell phone bill.

The massive drug amount pinned on John hardly tells the whole story, and it grossly overstates his culpability. It also fails to distinguish between a mere errand boy who was tossed some scraps, who didn’t have a car, who couldn’t pay his phone bill, and who lived in a dilapidated 1978 camper and the drug kingpin who ran the show and pocketed millions of dollars.

Additionally, there is a striking disparity between the amount of drugs sold by John that were proved at trial and the amount of (uncharged) drugs pinned on him via so-called uncharged relevant conduct at the relaxed sentencing phase. In other words, the amount of drugs John was responsible for at trial (about 6 kilograms of methamphetamine) represented a small fraction of the total amount ultimately piled on at his sentencing hearing (141 kilograms of methamphetamine). John’s PSR doesn’t even provide evidentiary support to support the massive amount of uncharged methamphetamine (an additional 135 kilograms) piled on at the relaxed sentencing phase. Rather, the PSR relies on the bald, conclusory statements that Hammer’s entire drug enterprise “distributed 5 pounds of methamphetamine a week for 52 weeks and 3 pounds of methamphetamine per week for the 17 weeks that John worked for Hammer in 2009, for a total of 311 pounds [or 141 kilograms] of methamphetamine,” and because “John was Hammer’s primary distributor, he is responsible” for all of it.

Because John had the much-feared federal judge John H. McBryde—one of the only federal judges to have been suspended for egregiously abusive behavior toward defense attorneys—in a very solemn yet panicked voice, John's attorney made clear that under no circumstances was John to object to anything in his PSR no matter how inaccurate because if he did, he would make the judge mad, and John would feel the judge’s wrath as a result. John objected to nothing and said nothing as a result. Thus, John was stripped of basic procedural fairness and due process, resulting in guilt by accusation.

Additionally, within the last two years, John was clinging to life after a bout with pneumonia, caused by the coronavirus, a virus that swept through the Federal Medical Center (in Fort Worth, Texas) like a flood. After months of being in a wheelchair and receiving breathing treatments, John finally regained some of his strength. He’s still not back to 100 percent. And the prisons still have not found a way to control the spread of the coronavirus, as evidenced by the new strains spreading through the prisons like wildfire.

What’s more, John has had exemplary conduct while in prison, participating in a host of classes, as well as being a long-term suicide watch companion. (While other inmates are put on suicide watch, John watches over them.) This hardly captures the full extent of John’s extraordinary rehabilitative efforts while in prison.

John has paid a heavy price for his role. But his sentence is radically disproportionate to his crime. We need someone to champion John’s case for a grant of Clemency or Compassionate Release.